Essays

Alternator essays are commissioned to support gallery programming including our Main Gallery exhibitions and Community Outreach activities. These essays take a variety of forms: formal essays, Q&As with the artist, interpretive responses, and other types of creative writing pieces.

Interested in writing for us? Learn how to join our roster of writers here.

Kelly Terbasket has crafted a new interpretive essay on the Similkameen Artist Residency’s current exhibition The Guest Book. Kelly reflects on her mixed heritages—syilx and settler—and how “code-switching” became a mode of survival for her. At the Similkameen Artist Residency, she leaned into her art to bring her to a place of authenticity, unburdened by the “colonial need for perfection, exhibiting, [and] commodifying.”

An interpretive essay on Tara Nicholson’s exhibition, Mammoths, EcoZombies and Permafrost Extinction written by Caolan Leander

In Tara Nicholson’s Mammoths, EcoZombies, and Permafrost Extinction, the Arctic is seen through large-scale photographs that reveal the North in a state of crisis. Trading the frozen vistas of icebergs for intimate photographs of animal parts, riverbanks, and ice cores, her images invoke an existential uncanniness that destabilizes the viewer as we witness multiple absences through the temporary presence of decay, erosion, and thawing ice.

As part of a new series of essays taking inspiration from the Alternator archive, Michaela Bridgemohan considers Crystal Przybille’s practice, and the connections between two of Przybille’s recent public art commissions: The Father Pandosy Mission 150th Anniversary Commemorative Sculpture (2012) and The Chief Sʷknc̓ut Monument (2019).

Three Way Mirror is the collaboration of three queer artists from across Canada born in the 1970s – Daniel Barrow, Glenn Gear and Paige Gratland – who first connected in 2018 over a shared commitment to craft and ways of making like hand-drawn animation, sewing, weaving, leatherwork, beading, and paper dolls.

As part of a new series of essays taking inspiration from the Alternator archive, Lucas Glenn interviews prominent syilx artist Sheldon Pierre Louis to discuss his practice, and what it means to make space for syilx and Indigenous artists.

'(un)resolving liminality', an interpretive essay on Jordan Hill’s exhibition, The Missing Distance, written by Aly K. Benson.

In an evergrowing world, with each passing chance for advances to take over, we as a people expand our abilities, and our minds have no option but to choose a narrowed lane of focus. To better state, yet paradoxically: as the world gets bigger, it gets smaller.

As part of a new series of essays taking inspiration from the Alternator archive, Erin Scott explores the ever-evolving community-based arts practice of Mariel Belanger.

As part of a new series of essays taking inspiration from the Alternator archive and activities, Andrea Routley considers Community Partnerships, and the value of creating a welcoming space.

As part of a new series of essays taking inspiration from the Alternator archive, Lucas Glenn connects with Andreas Rutkauskas to explore the representation of the climate in creative practice.

As part of a new series of essays taking inspiration from the Alternator archive, Erin Stodola explores the work of Julie Oakes, founding member of the Okanagan Artists Alternative Association, the society that runs the Alternator Centre for Contemporary Art.

“Maybe we should stop trying to understand the world and instead trust the wisdom of algorithms”

(Megan O’Gieblyn, 2024, pg. 100)

CGish amalgamates the digital with the analog, using custom generative algorithms to splice together objects into perplexing, yet believable, forms. Heather Savard, writes on the state of AI and the future of art.

Michaela brings her own diasporic Afro-Carribean heritage forward with such sincerity. The scents in the salves of hair picks also pull from the landscapes of Kelowna. Patchouli, fir, and charcoal mix with black pepper, allspice, and shea butter. Scent mimics self as an olfactory Blackness is brought into this space.

Who gets to gaze upon whom, for what, for how long, and under which conditions? Can I look at your face as long as I desire? Can I see your wet mouth parting and closing and parting and closing? Can I watch your children fly above your private trampoline? Can I stare? I don’t know you and you don’t know me - what gaze is safe?

Dissonance in music is nothing new. No one cares. It's not a question of “right or wrong”. It's just a single aspect of a greater whole. Like silence. When exploited properly it serves to enhance the other components of the composition. If it works, it's valid.

Natasha Harvey’s exhibit of five works expresses the desire and sorrow of her lifelong relationship with the unceded land of the Syilx Okanagan territory. A mixture of acrylic painting, spray paint, collage of found building materials, linocut print, drawing, and photography, her layered, complex, airy canvases create a ghostly landscape of lost forests, half-built wooden houses, patchy snow, torn fences, and oversized undergrowth.

Rather than romanticising houses in the woods, these works draw attention to the vulgarity of wooden houses built over the scraps of a razed forest. Rather than hiding the process of clear-cutting, excavation, and construction, Harvey’s compositions seem to peel the skin from the body of built suburbia, showing the violence of ongoing colonial land capture.

The Devil came to me in the form of a tomcat. He was big and orange, short-haired, proud chest, smiling mouth. He had lovely pink satin ribbons tied round his throat, ankles, and the tip of his tail. I’d opened the door for my gray tabby, Misty, and in he came behind her.

But what did you come here for?

I’m often asked.

Les Îles-de-la-Madeleine…

You mean?

Well, it must be for the nature; the remoteness, the space, the experience, the beauty.

On December 3rd, 2022, Katherine Pickering met with M.E. Sparks over Zoom to discuss her exhibition of new work at the Alternator Center for Contemporary Art. This is an excerpt of that conversation.

I swear I saw something. It was right there, in front me. Nothing scary, nothing bizarre, I think. More like a form, something that has a presence, a form. It was tall. Not that tall. A bit shorter than that maybe. It was right there. I say a form but that might be misleading.

What is time, and how do we experience it? Recent and ongoing events have made us all aware that

time is as fragile as it is precious. If the order of time were to collapse, for whom would it matter?

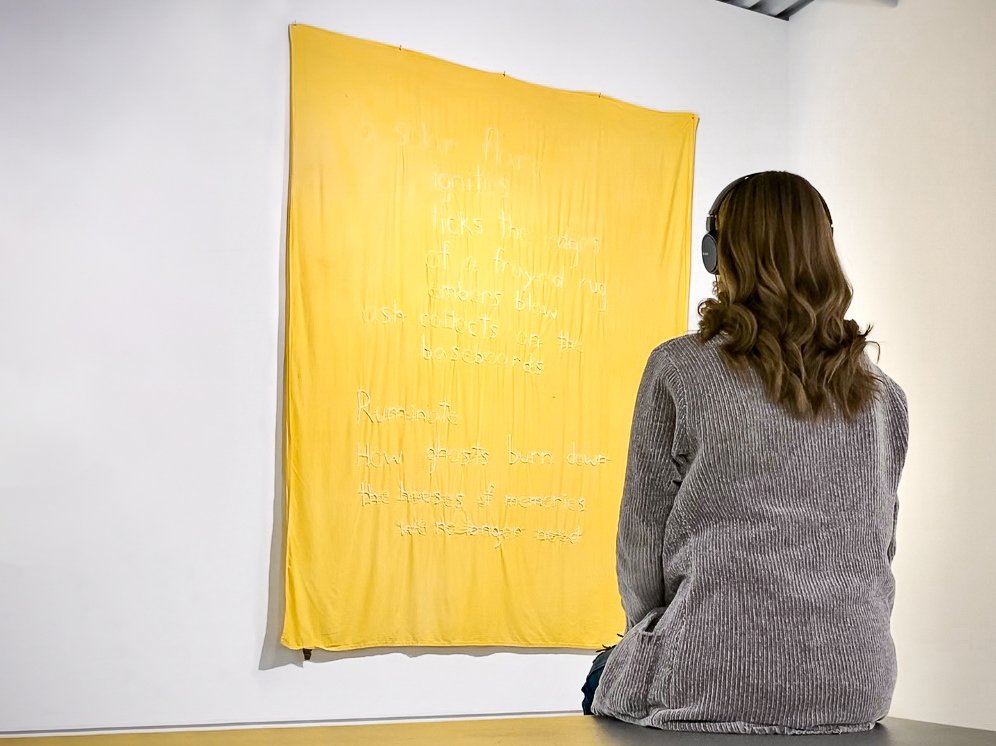

In my artisan life, there is tension between textiles that survive and that have the potential to rot away.

Weaving in progress, like all works in progress, are compelling visions which can offer aspiration and dread simultaneously. It is a stark dichotomy of tangible formulations and opened parallels. Like all forms of craft, it is the result of practice, iterations and repetition.

As an adult, my art practice has evolved out of an interest in nature, a sense of conflict over contributing further objects and materials into a culture of “too much”, a sensibility to use what is around me, an innate desire to make, and a belief that investing energy and care into materials is deeply meaningful.

As an adult, my art practice has evolved out of an interest in nature, a sense of conflict over contributing further objects and materials into a culture of “too much”, a sensibility to use what is around me, an innate desire to make, and a belief that investing energy and care into materials is deeply meaningful.

“There can be no repetition,” wrote Gertrude Stein, “because the essence of that expression is insistence, and if you insist you must each time use emphasis and if you use emphasis it is not possible while anybody is alive that they should use exactly the same emphasis.” Here, in Figure as Index, images repeat.

Our current archeological record suggests that the earliest human-made mirrors were created approximately 8,000 years ago in southern Anatolia, or what is now south-central Turkey. These Neolithic mirrors, unearthed in the settlement of Çatalhöyük, are round or ovoid, approximately palm-sized, and were painstakingly crafted from obsidian, a deep black volcanic glass, with very finely polished, slightly convex surfaces.

Just as in life, art is a perpetual unfolding of that which came before. My painting exhibition at the end of 2021 at the Alternator Centre for Contemporary Art was titled, This is a Love Story, and I have recorded a series of walks that are an extension of that; the search for meaning, and the decision to rest in the space of Love during the present time when it often feels easier to choose fear.

“Construction and infrastructure development is our most impactful human activity. We must learn to alter our approach so that we ‘Design for Life, not Machines’.”

Teresa Cody reflects on the exhibition This is a Love Story, by artist Lindsay Kirker.

It is essential to the understanding of S.C. Jean’s work to acknowledge that she is a self-taught artist. This is to say, that she did not go to art school or university to study art, but instead picked it up independently and found her own way to create. Because of this, she has developed a unique language, and consequently, her work may not tick every box of what you expect to see from a “schooled” painter. Yet if you are willing to spend time with her paintings, you find that they stand on their own merits and offer a rewarding viewing experience. I would go on to say that it is precisely through this lack of training that she has developed a distinct voice that transcends many of the derivative works that have been spawned by the academy.

Levi Glass’s Legroom for Daydreaming invites curiosity and encourages enquiry. This intriguing assortment of visual puzzles and strange devices stirs our desire to investigate what we see. Here, ordinary materials and mundane, domestic items gain the capacity to inspire, awe, and delight.