Weaving Together // Flannery Surette

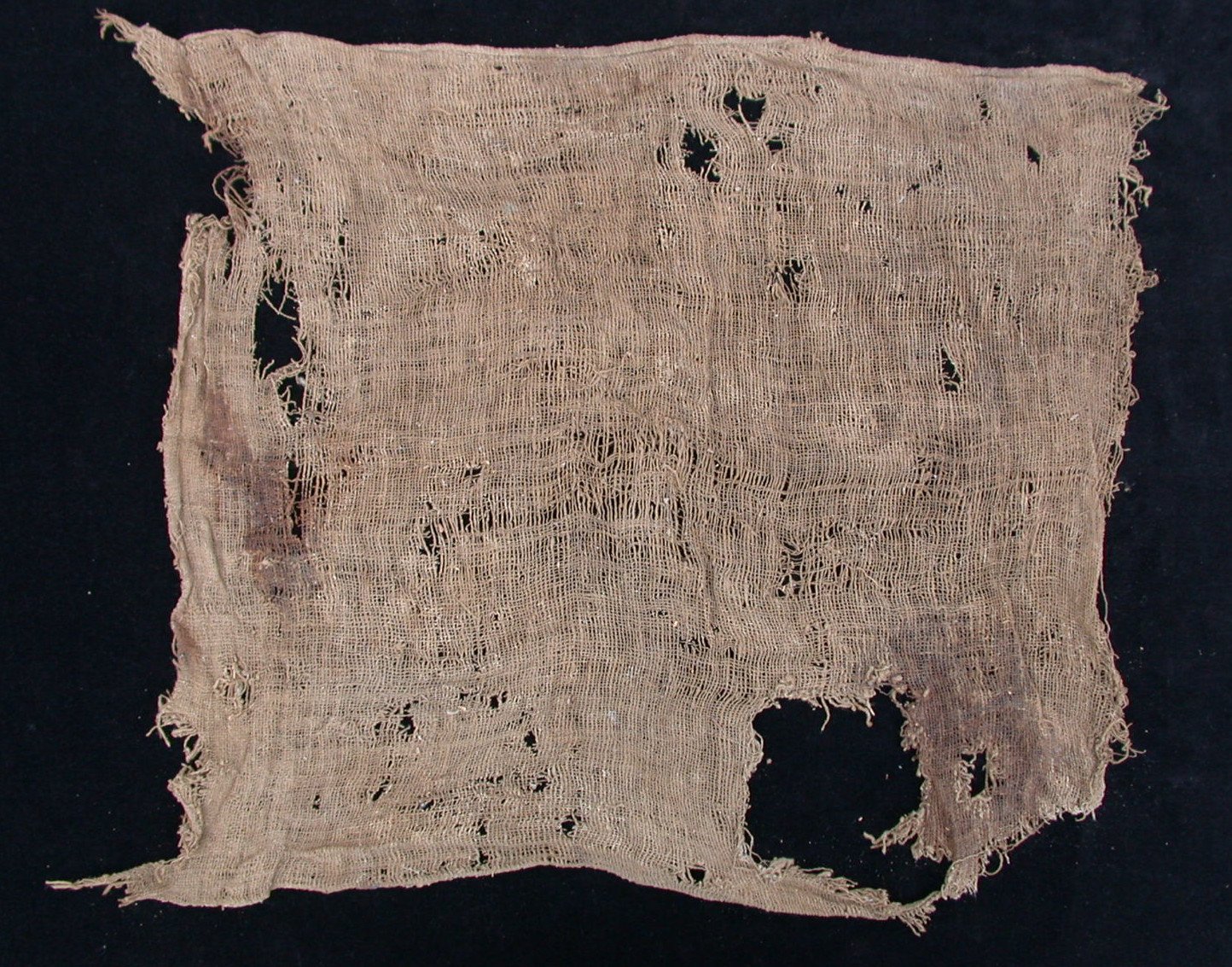

Child’s shirt excavated from the site of Huaca Santa Clara in the Virú Valley

This is a child’s shirt excavated from the site of Huaca Santa Clara in the Virú Valley on the north coast of Peru. The site was an administrative centre for the Virú polity and it sat in the middle of the valley on a natural hill, controlling trade form the coast to the west and the mountains to the east.

Visually, this shirt is stained and is missing an entire sleeve. It was cobbled together from more than one textile and not particularly well. We know nothing about the child who would have worn this shirt as most of the textiles from this site were recovered from fill and from an archaeological perspective lack more precise context. However, despite its ragged appearance, this shirt was one of the few identifiable artefacts; the fact we can say it is a shirt can rarely be said with confidence for the assemblage I examined.

I am interested in the development of technological practice including how much time and labour spinning and weaving entails. This falls into the category of a utilitarian good. It is made of simple plain weave and a naturally coloured cream cotton. It was meant to be worn and used on an everyday basis, so roughly the equivalent of a modern t-shirt. However, the child who would have worn this shirt might have been involved in the process of creation of this and similar garments. In contrast, most modern folks may be completely unaware of the global forces that come together to produce their clothing choices, let alone making their own from any stage in the process. In this essay, time and labour bestows value to an object where now buying clothes is frictionless, seamless; we are not obligated to think of the work involved.

I chose this object as an icon or as a representation of textile craft from the region as it speaks to the power of everyday objects, illustrates the time spent in making humble goods and transcends time and space in a way that more fantastic objects may not. Objects like these make textile craft attainable while illustrating the time and community labour that each entailed. I don’t wish to romanticize the past where we would have participated or at the very least would have been aware of where the objects in our lives came from nor do I wish to romanticize specifically the time spent making textiles. I want to emphasize that the Virú people and other Andean peoples would have had an intimate understanding of the time and labour needed to produce textiles essential in daily life. To be free of textile production itself is a luxury.

It is also not to say that Andean peoples were not wasteful in modern eyes; textiles were often burned and destroyed as part of religious practices and elites could be buried with dozens of textile, many of which included precious metal bangles, imported feathers, colourful woollen embroidery, fine and rare fibres and complex weaving techniques representing the ability to accumulate resources and labour that was ultimately interred with the dead. They valued colour and shine and decoration as much as modern people.

Those fancy textiles do command more research attention and museum display space. In contrast, plain weave cotton textiles reveal little on first glance but do yield intriguing sets of data and patterns. They represent hundreds of work hours to produce, beginning with agricultural investment to the final assemblage, work that was often interspersed between other daily activities. For textile practitioners in the Andes, weaving was an activity for the “broken” times between household tasks and childcare was, generally, the purview of women. Full-time and expert weavers tended to be women past the age of birthing and childcare, the widowed or the never married, though spinning could be practiced by anyone. She would draw upon the basics learned as a young woman taught to her by other older girls while they watched over a community’s flocks. In the past under the control of peoples like the Inka, the Wari, the Chimu, and the Moche, textiles were also produced in workshops by artisans supported by the same state apparatus but peasant folks still produced their own. Textile guilds still reflect some of these patterns as time is at a premium when you have a young family; the majority of guild members are often both retired and identify as women.

Mantle

Do modern hobbyist handloom weavers think much about time? I reflect on the limited hours to engage in a hobby or a deadline for a gift, but there is no pressure in this equation where readily made cloth is available for clothing and the local Inka tax administrator is not arriving soon to collect the yearly tribute. We can quantify time using a different textile, this simple mantle, measuring 42 cm x 36 cm. Using rates from the work of Bird and Losack (1984: 342) of women spinning cotton on drop spindles and from Vreeland (1986: 370) who studied the supported spindle technique of Mórrope on the north coast, this mantle would take 4.5 to 6.6 hours respectively to spin the cotton singles alone. From studies of Guatemalan weavers, it takes 30-40 hours to weave “one square meter of medium quality cloth” in cotton on a backstrap loom with a total investment of 200-300 hours when spinning is factored in (Costin 2013: 181) and similar wool cloth from the Andean highlands required a time investment of between 225 and 260 hours (Costin 2013: 181).

No wonder, then, do we see many examples of reuse and repair; to return to the child’s shirt, it and another similar tunic were both composed of textiles patched together to form a full garment. These garments contradict typical practices in the Andes where cloth is woven with all four selvedges finished and then the whole pieces of cloth would be sewn together to form the desired type of clothing, resulting in no waste. There is no Indigenous tradition in the Andes of cutting cloth into a pattern that can then be sewn together to form a tailored garment. In this region, rather, the garments are square and shape attained with the use of belts, strategic slits and side seams. What then was recycled to make these garments and why? Was it seen as a suitable garment for a child who would soon outgrow it? Was this child on the margins of society? Was this a method of reuse that was common but obscured by the imperfect nature of the archaeological record as these garments were further recycled or failed to preserve?

These textiles speak to my modern practice of using mostly natural fibres and trying to make a “good object” that survives. This also appeals to me professionally as the preservation of textiles and other organic materials is highly contingent on material type and environmental conditions. This is the reason why stone tools and pottery are the icons of archaeology - they last and do not rot away. Archaeology is a science of fragments, slivers of things that provide insight into the lives of our ancestors and I am delighted to work in a region where organic remains last. I would argue, too, that sustainability would have been a foreign term to peoples of the past and yet their value to their owners and society was clear, as many plain weave textiles were well worn and exhibit attempts at repair and reuse, exemplified by the child’s shirt, made of several plain weave textiles refashioned to fit a younger person.

In my artisan life, there is tension between textiles that survive and that have the potential to rot away. I want to make “good” objects inspired by Japanese art critic and philosopher, Yanagi Sōetsu’s concept of mingei or folk craft. Humble objects that gain some of their aesthetic value through use, the ability to be repaired and their quiet presence in our daily lives. Over time they may become heirlooms to be passed on to a new generation. At times, I feel as if the tools I use, like the 60+ year loom, fit the mingei concept more thoroughly while the objects often seem fleeting in comparison as they are crafted to my taste alone. Perhaps, there is also the value inherent in rot. Perhaps, I don’t desire my pieces to survive beyond my lifetime but have the potential to be recycled back into the earth and to never reveal their secrets to archaeologists of the future.

A shirt like the child’s shirt embodies this good object. It had a function and was not only repaired but made of other textiles. It attempts to reclaim the time, labour and resources that were part of the original cloth, made anew if not in the most beautiful form. As an archaeologist, I can quantify the time and technique and as a weaver I can admire it and be grateful I am not reliant on always making my own cloth. I am also ambivalent around my own practice and the potential for these objects to speak to us now and our goals of sustainable practice and use. To be able to engage with good objects and have the skills to repair them is a privilege shaped by systemic forces like class and capitalism that force our choices. To be a hobby artisan is also a privilege and it would be a lie to say I don’t mostly wear manufactured goods. Textile craft often seems like magic and maybe the best I can offer to dispel this, to make the costs of it clear to make it seem accessible to all comers.

Dr. Flannery Surette joined Okanagan College in Fall 2019 where she teaches introductory archaeology, biological anthropology, and cultural anthropology along with specialty courses focusing on women cross-culturally, culture and the environment, the anthropology of art and archaeology of the Americas. She specializes in the archaeology of the Peruvian Andes where she studies the development of weaving and spinning and other fibre technologies, the formation of identities in early Andean states, and the transmission of this knowledge over time. She is also interested in the anthropology of art, contemporary fibre artisans, experimental archaeology and the development of pedagogical materials for anthropology. In her free time, she is a weaver and spinner and a member of the Ponderosa Spinners, Weavers and Fibre Artists Guild of Kelowna, B.C.

This is the second annual Weaving Together series, which brings to the forefront sustainable fibre art practices. Engaging the community to demonstrate accountability to the environment, show a coming-together through a variety of activities: online chats, essays, videos, in person workshops, and hands on community weaving opportunities. For more information on Weaving Together, visit Cool Arts Society.