How to Be in an Art Gallery // Andrea Routley

As part of a new series of essays taking inspiration from the Alternator archive and activities, Andrea Routley considers Community Partnerships, and the value of creating a welcoming space.

Maybe you’re perplexed by contemporary art. You might wonder, Am I meant to solve the riddle of its meaning? To deduce how it was made? Is this good? If I don’t understand, is there something wrong with me?

But that’s okay. The point isn’t to figure it all out, but to enter the gallery with a sense of openness and curiosity and uncertainty. Because the Alternator Centre for Contemporary Art is also more than a place for art. It is a public space committed to “everyone welcome,” a space that doesn’t ask you to buy a drink or a ticket to enter. One month, sculptures of beeswax and wenge wood, in another, 3D-printed vessels, yarn, video…And between exhibits, the walls are white as a page—what might be written here next?

Just be present, be curious.

Come in.

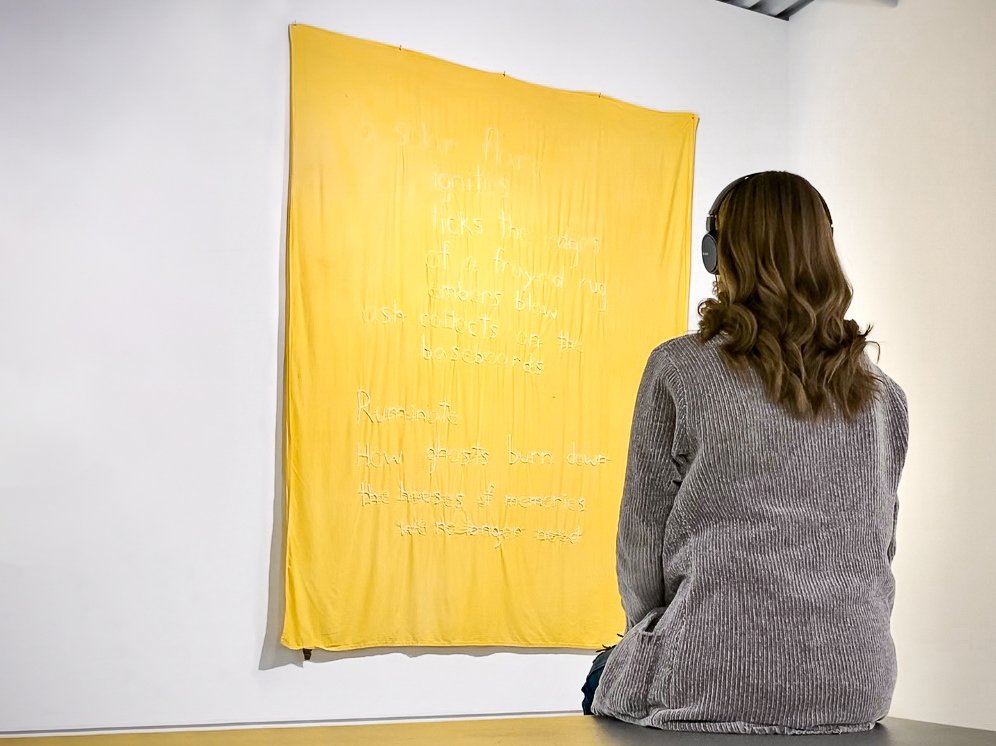

Installation view of a sound falls but leaves no bruise, Whitney Brennan, 2022.

This sense of openness, creativity and possibility is what draws many community groups to the Alternator, not only to exhibit art but to facilitate meaningful community connections and dialogue.

From 2012-2018, UBCO professors David Jefferess and Allison Hargreaves led the AlterKnowledge Series. The aim was to provide a venue for ‘alternative’ knowledge to be shared and valued, and for dominant systems of ‘knowledge’ to be altered. It focused on critical engagement with the way colonialism shapes relationships and identities, and it fostered community-based knowledge-making, bringing people together to discuss, share, and learn.

The series began as lectures: experts would present, and people would sit in rows and ask questions at the end. “And I hated it,” David says.

Our physical spaces impact the ways we interact. To illustrate, David describes his feeling about one library space. “Every time I’ve gone in there, it’s set up in rows with a podium. And there’s a mindset for people when you go into that space—you have an expectation about what’s going to happen.”

To create a new expectation, AlterKnowledge arranged a circle in the gallery. “We had [guest speakers] initiate conversations by talking for twenty minutes, and then we had an hour for facilitated discussion. It was very purposeful…it was a participatory space designed for dialogue.”

But it’s not only the physical space that facilitates such participation. We attach meaning to these spaces, too.

AlterKnowledge participant discussion at the Alternator Centre for Contemporary Art, 2016. In the background, What Does It Mean To Be The Problem?, Fern Helfand, Tannis Nielson, Samuel Roy-Bois, 2016.

For about five years, Kinfolk Nation, an arts collective founded by Trophy Ewila and Lady Dia, organized House of Hope, a regular community gathering of BIPOC artists. Held in a private residence, these gatherings were a place to discuss and workshop their creations. They valued diversity, interdisciplinarity and community connection. The guiding philosophy, as Trophy explains, is Ubuntu, which means “I am because you are.” In other words, Trophy says, “‘a constellation is more beautiful than a single star.’ If you’re light shines, that reminds me to shine my light, not to dim it.”

In 2021, in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, the need for connection among the BIPOC community intensified, and House of Hope looked for a space that could accommodate such gatherings and facilitate greater public impact.

“Some places talk [about inclusivity], but when you actually get into those spaces, the practices do not corollate with the words,” Trophy says. When organizations foreground diversity and inclusivity—especially in relation to Africa—traditional cultural and art practices are often highlighted, such as during Culture Days. “But [these cultures] are current, they’re contemporary. They’re dealing with present and future engagements.” Despite good intentions, a focus on traditional aesthetics and practice can result in a presentation of diversity that feels performative because it fails to engage with contemporary realities and conversations within that community.

From March 18-April 30, 2022, the Alternator exhibited Figure As Index, the documentary photography work of Luther Konadu, which focused on Black community and experiences in Winnipeg. Konadu asks, “how he can create an alternate past in order to imagine a different future of self—as it relates to a broader social communal context.”

For Trophy, seeing contemporary Black stories told by Black artists in the gallery is one way the Alternator is coded as such a non-performative inclusive space.

Since that time, Kinfolk Nation has organized several community events here, facilitating interdisciplinary and intercultural engagement. Most recently, their Abaantu Series Vol. III took place November 2023. At this time, the Alternator was exhibiting Cameron Gelderman’s Yarnlandia, an explosively colourful yarn installation. Here, Abaantu participants engaged in a musical collaboration, drumming, singing “Underneath the tree,” and joyfully circling the centrally located, psychedelic yarn sculpture. The image of participants together in song around this intricately tangled tree—a symbol itself of familial pasts and futures—seems an apt metaphor for the community connection made possible here.

After Yarnlandia, as with every exhibit, the gallery again becomes a white page. Maybe there are some marks on the walls where things were mounted. Maybe some stray yarn remains snagged on a nail someone missed.

It’s quiet in the gallery.

It feels like nothing is happening. It’s easy not to notice the door to the office where staff—Lorna, Moozhan, Arianne and Ella—are working, not only with spreadsheets and grant applications, but phone calls, Zoom meetings, conversations with artists who pop in, cultivating relationships not only in Kelowna but across Canada and internationally.

I love the philosophy Trophy shared, “I am because you are,” for the way it succinctly asserts the fundamental importance of relationship. Because, as I chatted with artists and community organizers, aside from the practical functions of the gallery space (its affordability, accessibility and dynamic design), and the potential it represents (encoded as a space embracing diverse ideas and peoples), what everyone emphasized were the relationships underlying the values embodied here.

“I’ve worked with multiple gallery staff since around 2008, and they always just seem like genuine, real people,” David says. “They were always interested in ‘how do we create good relationships with various communities?’ And I think that’s a real value of that space.”

Trophy also credits the staff for a community engagement that is meaningful through its continuity: “Our lives are continuous and dynamic as well, therefore there must be continuous engagement with this shifting culture to allow multiculturalism to be non-performative.”

For other public institutions, community engagement can at times be cynically viewed, as David suggests, as a “branding opportunity.” I’ve encountered this even in small non-profit organizations, where, regardless of the good intentions, community-engagement activities can still conclude with a sense that another box was simply ticked. Perhaps part of the issue is the way we measure the success of these events. In reporting to directors, for example, we may include graphics illustrating attendance and social media reach, and then conclude with a handful of testimonials and photos. But what happens to these relationships in six months? One year? Five years? How do we measure—and, thus, value—the human connections that enable us to reach our full human potential, to “shine our light” in constellation?

I wonder if contemporary art has an answer—

After all, how do we value a tree of yarn? A flower dipped in beeswax? Shadows of pins pencilled on a wall, the gallery’s white page?

Once you come in, you cast shadows, too. You’re present, curious, uncertain.

Yes, maybe that’s how: By looking at you, something like a work of art.

Andrea Routley is a writer and teacher based in Vancouver and Kelowna. Her first book, Jane and the Whales, was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award for Debut Fiction, and the title story of her second book, This Unlikely Soil, was a finalist for the Malahat Review Novella Prize.