Shirl wakes in the bare rectangular room. White walls, grey painted floor, heavy white molding framing two large windows divided into four square panes. Dawn light defines two identical sets of squares creeping up the opposite wall. Below the windows the white painted radiators gurgle to wakefulness. Shirl has moved most of the room’s furnishings to the hallway, including the bed frame. All that remains is an imitation wood table, two chairs, and a mattress on the floor. She prefers it this way, to be unencumbered during this time by the past lives of objects.

The smell of new PVC plastic counters a slight pervasive mustiness. In the shadow of the far corner, the bulky sculptural form of thick pink skin masquerades as a low rise of steps. It came together quickly, still raw in its presence. What is my relationship to this new thing? Shirl asks herself. Yet the title “HOST” has already attached itself, as in holding or accommodating.

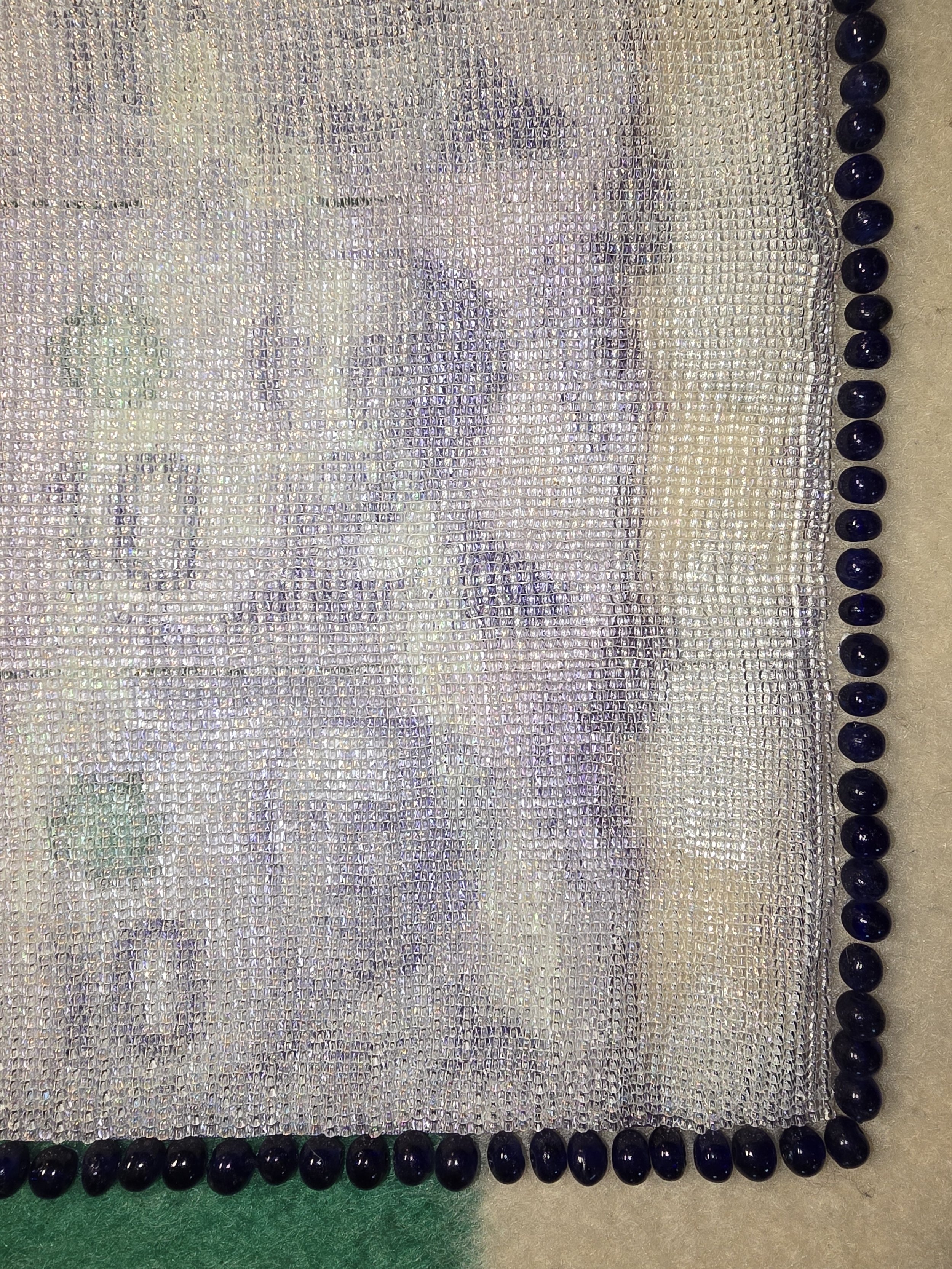

Pinned above the sculpture, high on the end wall is an enlarged black-and-white copy of the photograph she took of the staircase next to the Dnieper River. On the other end wall is a drawing surface made up of fifteen sheets of 300-gram watercolour paper taped together from the back and mounted as a grid. The composite stretches over eight feet tall by six feet wide. Beginning work on it the day she arrived, Shirl’s intention is to mark time over this month of thirty days, plotting her psychic passage through the city. She studies the initial laying of vermillion red and ochre swatches in broad arm sweeping strokes, details of graphite lines cupping a distinct edge of apple green, drips flowing uninhibited. A delicate wooden ladder leans against the wall next to the drawing, a means of gaining height to reach the upper half. It was the final concession to the useful things she allowed to remain in the studio, harbouring something of the staircase’s liminal structure to get from one point to another, up and down, and up again.

Shirl rises and dresses in the dim light.

Outside the air is cold, the day greying with promised rain. Shirl sets out along Kopenhagener Straße, as she has every day so far, stopping first at a favourite coffee shop around the corner.

Berlin’s frenetic pulse quickens her pace. She lets intuition guide her trajectory rather than a set plan. The act of walking is a key element to her art practise, whether at home or in the unchartered territories of elsewhere. She perceives a nostalgic rumination to these wanderings, acknowledging a melancholic past pushing in on her thoughts. Berlin is a city whose social fabric beats in conflicting turmoil. It both distracts from and awakens in her losses she carries, finding a restless solace in the city’s struggles.

Wrapped in plastic, the cardstock staircase is a reassuring object tucked in Shirl’s backpack. A side street discloses a row of unopened storefronts, the day still early. In one, a mannequin stands with arms stiff at her sides, confronting Shirl. Its plain formal attire gives an impression of authority; from simple tailored cuffs, hands hang lifelike, pale, the fingers slightly bent. Shirl stares at them.

As a young child, the palms of Shirl’s hands held a power over her gaze. She would see them as other than herself, later referring to it as “hand staring”. There was an element of fear involved. She took care to not overdo this activity, to not become desensitized to the feeling it evoked, understanding even as a child it would serve her, its seed developing into an acute sensitivity to the world around her.

Shirl unwraps the model and presses its length to the window. There is an immediate interchange, the stairs reflection erasing the solidity of the mannequin’s dark torso, the pale hands left unscathed, like a ghost trying not to be seen. With one hand supporting the model she takes a hasty photograph. Unnerved by the interaction, she hurries on.

Brandenburg Gate looms in the near distance. Crowds are funneling through to witness the date, the 20th year anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Shirl turns instead to enter the pastoral Tiergarten park, consciously refuting a desire to investigate the plaza until later.

Pungent decomposing leaf litter lures her as she disturbs a congregation of geese, their fluttering squawks beating overhead. Meandering pathways break into damp grassy fields. Shirl veers towards a maze of enveloping thickets, trickling sounds of water enticing her further afield. The spot she is looking for will make itself known. Reflecting patterns of dark and light cast by bare branches of hovering oaks and chestnuts signal a haptic terrain. A hushing solitude embraces a bucolic pool, a reservoir for mourning.

Shirl selects a stick to support her cardboard staircase, balancing it cautiously on the sandy substrate. She crouches down. Her camera viewfinder slowly pans back and forth; the grey rigidness of the stairs imposes its dominant stance as she moves it further and further out of the frame. Back and forth until her eye detects a sharp edge between truth and fiction. A sense of the impossible recaptured? She moves the placement. Tries again. And again. Click.

Exiting the park, amplified music and voices assault as Shirl enters the mass pulsing within the cordoned off streets. Her energy shifts to that of the crowd, reading facial expressions, catching snippets of German and English, narrowing in on smells of grease and boiled sugar. “Look,” she says, pointing up. Everyone is looking up.

Articulated wings span out from dark statue-like figures crowning the buildings. Ha, she laughs to herself, the Berlin film, “Wings of Desire”. Just yesterday, she scoured the Staatbibliothek with her model, staging it amongst the book stacks, the very place the film was shot in 1987. Everything feels to be connecting. This is my Berlin, she thinks. The angel actors float down on cables, animating their silver feather appendages, their long coats and hair covered in chalky grey dust.

A reoccurring dream finds purchase as Shirl walks back over the George-C.-Marshall- Brücke at dusk. The dream is always about living in a city where she has never been, yet knowing the streets and buildings as if it were home. She pauses, scanning the River Spree, its arterial course pulling at the memory of her dream. Is Berlin her oneiric city?

At the threshold of the residency building, warmth calls Shirl in, her body weary. In the second-floor kitchen, greetings from the other six international residents are exchanged. “How was your day?” “What did you do?” “What did you see?” She sits for a moment accepting a cup of tea, then retreats to her studio.

Shirl goes to the wall drawing, climbing the first few rungs of the ladder. Reaching out with her left hand, her pencil traces the day’s unfolding without conscious thought or reason, whatever comes to mind. Marks rapidly overlay the thin washes: images of boards torn apart, falling into oblivion; a pole or stake piercing an organic shape, an edible treat, or a wounded limb; the outline of an animal, its pointed snout raised in a scream.