Tony Stallard // New Breed

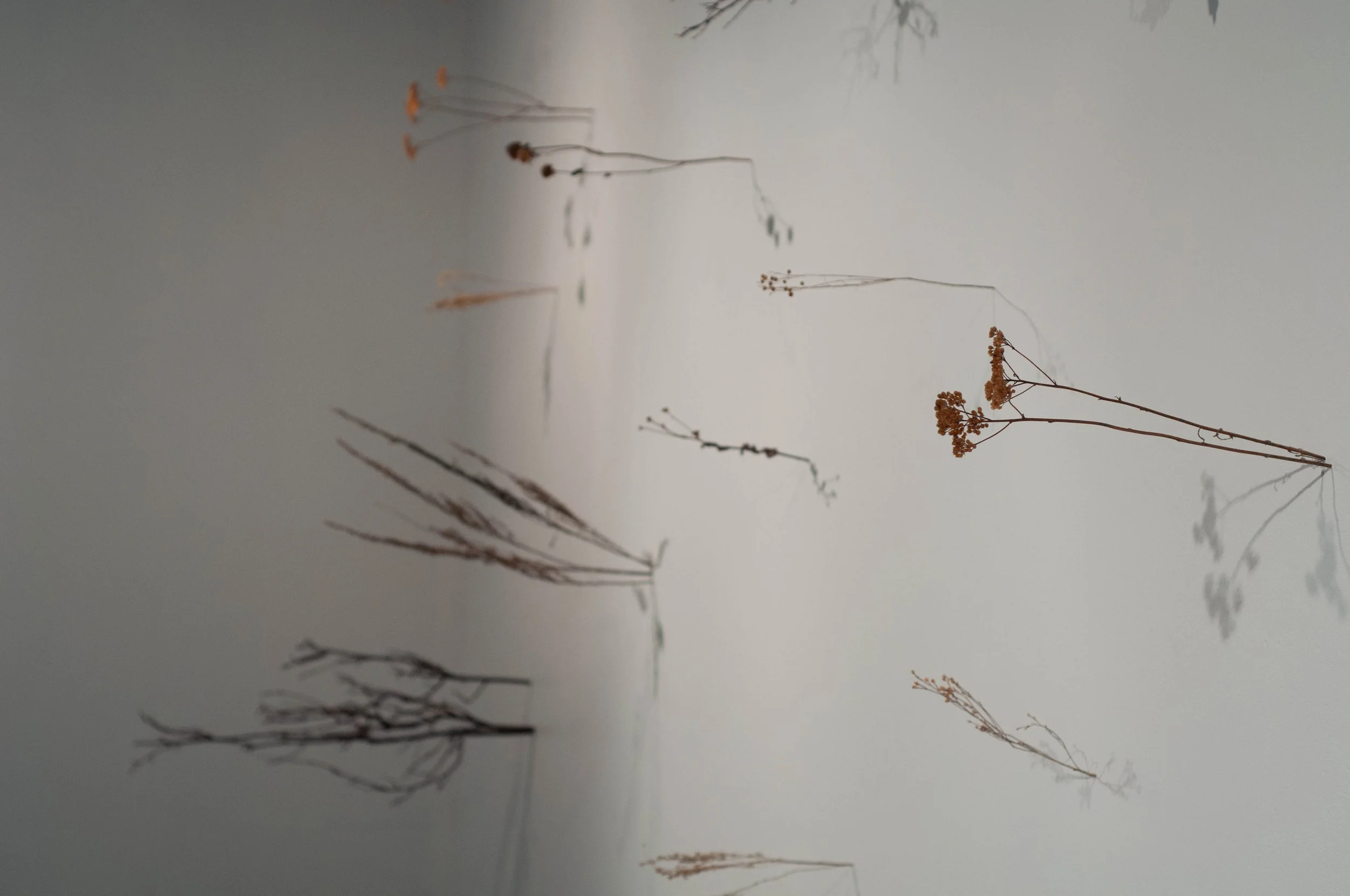

Tony Stallard’s New Breed experimented with the relationships between light and material. In creating his sculptures, he purposefully selected organic materials like moss, timber, feathers, and bones to contrast with industrial materials like neon, steel, ceramic and glass. The materials contained a dialogue between manufactured and natural: calling to what Stallard referred to as their “alchemical properties”. One wall in the gallery space was dedicated to poetically written stories conveying community members’ most surreal experiences with nature.

Though based in the UK, Tony Stallard has exhibited work internationally, and has 25 years experience making site-specific sculptures. He has studied in London at Chelsea School of Art, has an MA from Wimbledon School of Art, amongst others. Stallard’s current work involves mixed media with light for exhibitions, urban sculpture trails and sculptural commissions. All of which are site-specific light sculptures.

For more information about Stallard’s work, visit his website.

A Conversation Between Nature and Manufacture, Disturbed and Fractured // Lucas Glenn

There is a current dialogue growing between the natural and the synthetic. In the way that agricultural machines handle crops, and the way that telephone poles stand among trees, there are relationships that UK-based artist Tony Stallard simulates in his minimal, evocative, and unsettling exhibition, New Breed.

New Breed is composed of a series of sculptures featuring neon lights interacting with natural elements. Each sculpture is a micro-commentary, and as Stallard puts it, more of a warning than a statement. In Feed, red neon stretches along an assembly line of animal horns and metal piping, poignantly cautioning the increased use of genetic modification in meat industries. Similar in its thematic is Livestock, a work made up of tormented red neon formations that emerge from disheveled haystacks. The neon is reminiscent of fire, emitting ominous light. Stallard is no stranger to neon; his distinguished public works like Double Helix (1999), Titanic Kit (2009) and The Guardian (2010), are lit by it. He uses neon to create geometric, sequential, and iconic forms, and similar to artist Dan Flavin, subverts neon’s Parisian-barbershop and Las-Vegas-Strip history.

Stallard’s permanent public works embody the spirituality of place, reflect on the past, and contemplate the future of their locales. Many of them are neo-futuristic architectural beacons, abstracting light in the spirit of Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, revealing geometries in the spirit of Donald Judd, and signifying hope in the spirit of, well, good spirits. However, the combination of natural and synthetic in New Breed disturbs positivity, and conjures up images of a dim, dystopic world where nature and technology have monstrous relationships. Frankenstein comes to mind.

His artworks Wound and New Breed are particularly haunting, each for different reasons. A horizontal red neon strip bordered by two feathered headdresses, Wound is intended to represent Canada’s most severing territorial issues. In my relationalist purview, the artwork’s feathers and neon poetically continue the negotiation between natural and artificial. In my social justice purview, however, context is everything. Though Stallard’s aim was not to reference indigenous issues or “indigeneity”, to the engaged Canadian viewer it likely will. Intentional or not, the work’s context imbues difficulty. Problems arise because A) historically, from the Royal Proclamation, to Confederation, and onward, the British Crown forcibly took as much land as they could from First Nations while violating peace treaties and claiming authority over first nation lands, B) the colonial legacy continued to manifest in massacres, wars, human rights abuses, relocations, and residential schools, among other atrocities, and C) the use of headdresses and war bonnets in mass media were and still are key in perpetuating racist stereotypes of first nations (see: “red face”) (see: homogenization). Not for a second do I question that Stallard has good intentions in bringing to light territorial disputes in Canada, but by god the alphabet does not end at C. His exhibition at the Alternator takes place on unceded Syilx territory, amplifying the artwork’s potency.

New Breed, horizontally presented in the window gallery, is composed of a long stretch of peat, piled a foot and a half high, with a red neon tube snaking through it. The visuals bring to mind an iconic Ed Burtynsky photograph called Nickle Tailings #34 (1996); it depicts a river of blood-red nickel tailings winding through dark, scorched Sudbury (Ontario) earth. Stallard’s piece resonates visually and conceptually as well with Werner Herzog’s footage of the Kuwait oil sands. All of these pieces depict a hellish earth, ravaged by industry. Stallard’s installation has a vestigial tone, honest to Canada, industry, and the ongoing dialogue between the natural and manufactured.

Let’s talk about it.