Olivia Whetung’s gaa-waategamaag explored Mississauga-Anishinaabe place and landscape. Many Anishinaabe and Mississauga place names refer to the water; in fact, the name Mississauga itself refers to water. Navigating within Mississauga territory means having a constant awareness of the bodies of water, even when on land. Roads follow the contours of rivers and lakes, and traffic bottlenecks at bridges. However, the physical waterscape as well as the names used to refer to places have changed over time.

These works focused on one specific place name: gaa-waategamaag. According to historical record this name dates to the late 1800s and was given by Martha Whetung. It is more commonly pronounced and written ‘Kawartha’, and has been translated as ‘land of reflections’. This name, along with its multiple spellings, embodies a complex set of relations between people, place, and language.

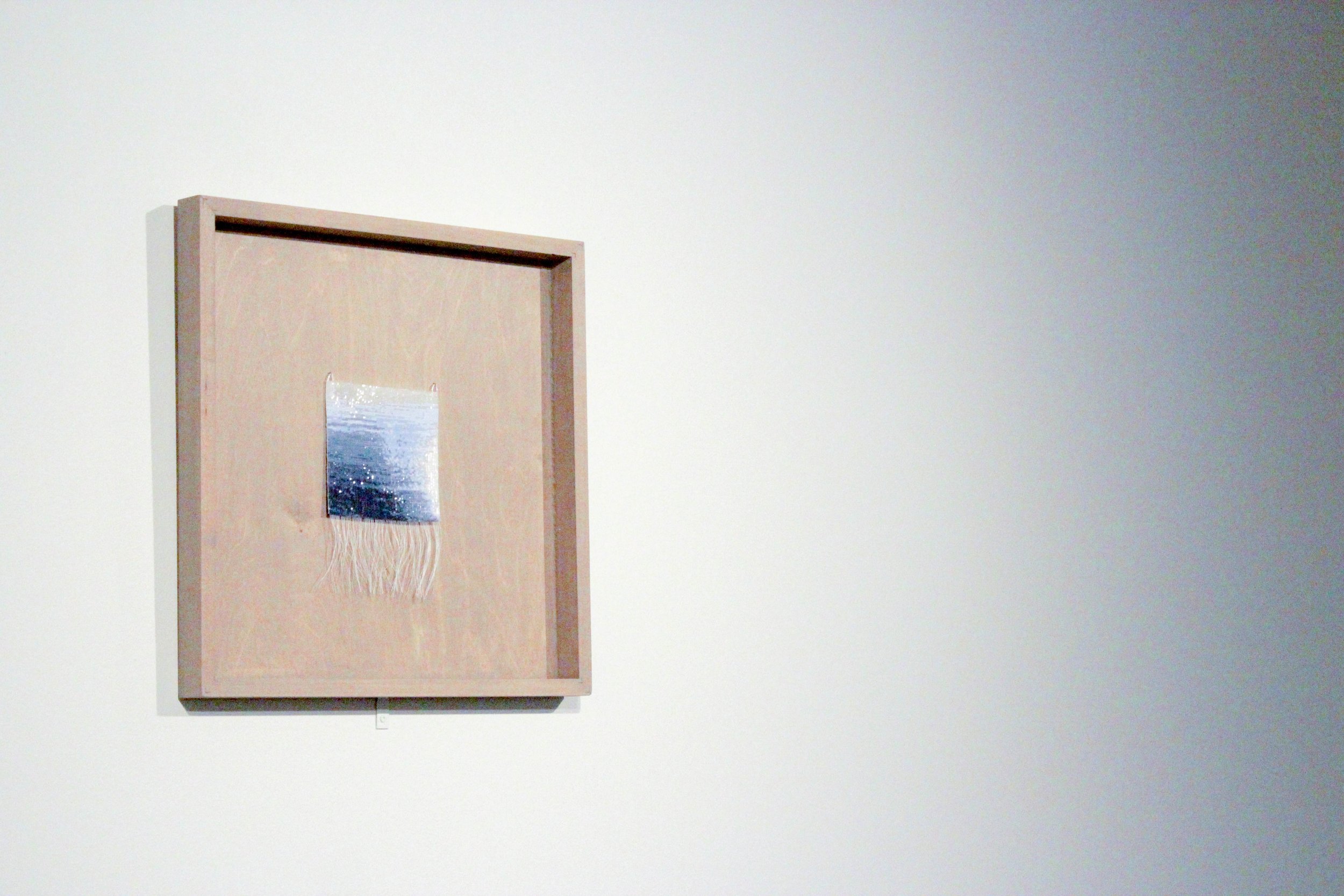

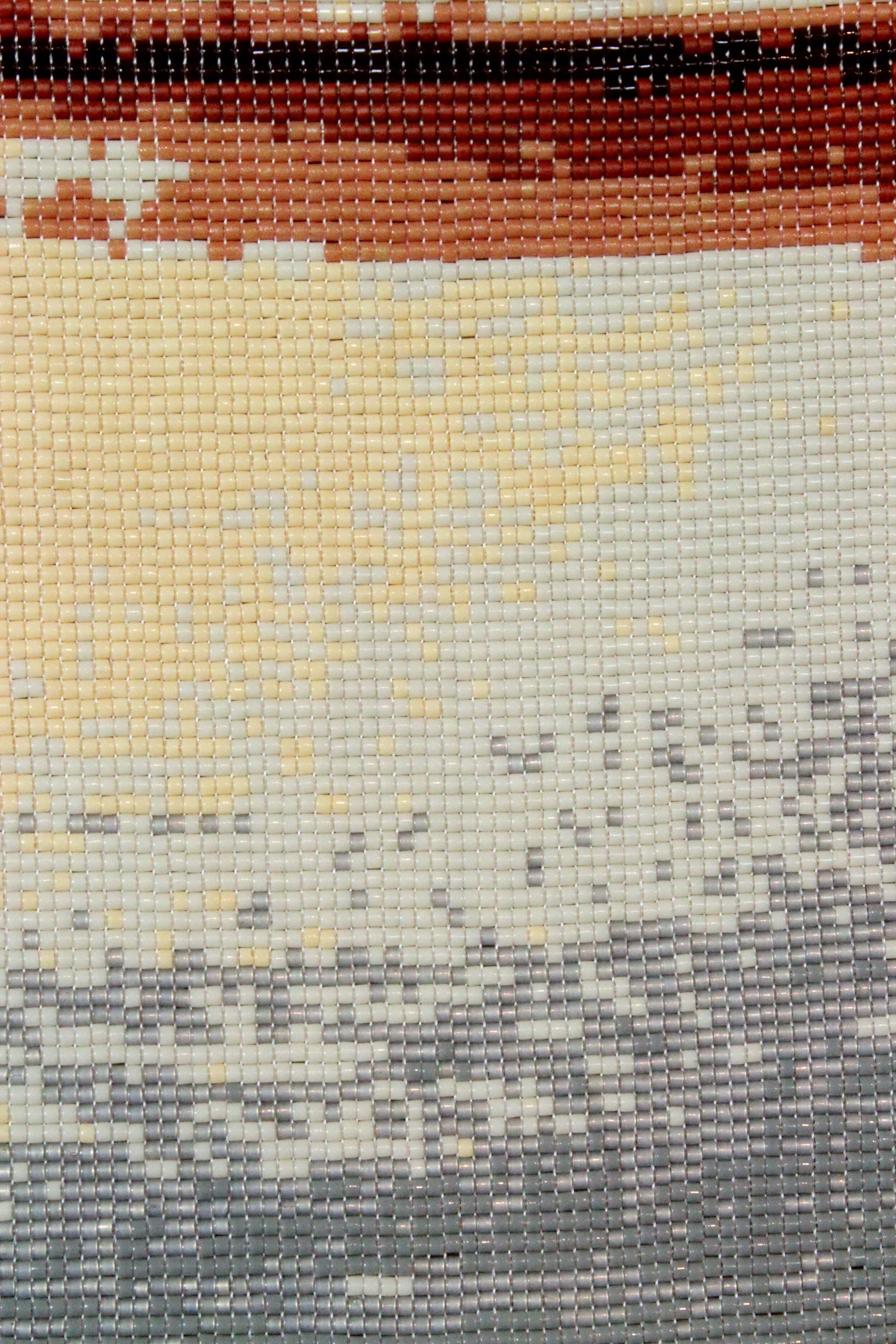

The Reflections series attempted to illustrate this name through beadwork. Whetung worked from digital photographs of light reflecting off of water in the area now known as the Kawarthas, editing the photos to create beadwork charts and translating those charts into loomwork. The resulting beadwork shimmered in the light and gave an illusion of surface movement as the viewer moved around it.

Olivia Whetung is anishinaabekwe and a member of Curve Lake First Nation. She completed her BFA with a minor in anishinaabemowin at Algoma University, and has an MFA from the University of British Columbia. Whetung’s work explores acts of/active native presence, as well as the challenges of working with/in/through Indigenous languages in an art world dominated by the English language. Her work is informed in part by her experiences as an anishinaabemowin learner. Whetung is from the area now called the Kawarthas, and presently resides on Chemong Lake, Ontario.

For more information about Whetung’s work, visit her website.

Lost in Translation // Interpretive Essay by Hanss Lujan

The title, gaa-waategamaag is the starting point for the work presented by Mississauga-Anishinaabe artist Olivia Whetung.

The term is traced back to the late 1800s, when tourism entrepreneur Mossum Boyd held a competition asking locals to submit a place name for the region found in south-central Ontario. Martha Whetung, a member of the Curve Lake First Nation and a relative of the artist, proposed the anishinaabemowin term gaa-waategamaag translating to “Land of Reflections.” The name was adopted for its definition and its branding quality but was then transformed to “Kawartha” as a means to make easier for English speakers to pronounce. Through this Anglicized process, the translation of the word also was re-branded as the slogan “Bright Waters and Happy Lands.” Around the same time, water locks and bridges were being developed along the Trent-Severn Waterway, a long series of interconnected lakes, rivers and canals; their construction physically changing the landscape to a recreational boating destination.

gaa-wategamaag features seven beadworks that depict images of water, including fragments of waves and ripples from the shores from the Kawartha Lakes and the Trent-Severn Waterway.

The artist explores the process of translation as she reworks digital photographs into beadwork, a medium she was taught from a young age and later reintroduced during her undergrad at Algoma University. The process of Anglicization can be interpreted by the initial pixelation of the digital photograph, where colours are flattened and minimized to a few select colours. The re-introduction of each pixel as a Delica seed bead can be seen as an act of reclamation; providing a dynamic experience of colours and textures that recall the original definition of the name place as “Land ofReflections.”

The scale of each work invites the viewer to have an intimate interaction with the image. These are contemplative objects; their vibrancy, colours, and beauty captivate your attention and invite you in. The shimmer of the beads creates a mirror-like quality. It’s easy for us to forget that as humans, we too are made of water; perhaps here we are given a chance to reflect upon ourselves, our relationship to water, and our responsibility to the environment.